Symphoria opens our March Casual program with Carlos Simon’s An Elegy: A Cry from the Grave, an evocative reflection dedicated to those who have suffered under oppressive power. Lutenist Michael Leopold joins us for Antonio Vivaldi’s Lute Concerto in D Major, and pianist Paul Di Folco performs the first movement of Felix Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto No. 1. Richard Wagner’s symphonic poem Siegfried Idyll completes the afternoon.

PROGRAM

SIMON: Elegy: A Cry From the Grave ![]()

VIVALDI: Trio Sonata in G Minor, RV 85 ![]()

VIVALDI: Lute Concerto in D Major, RV 93 ![]()

MENDELSSOHN: Piano Concerto No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 25 ![]()

WAGNER: Siegfried Idyll, WWV 103 ![]()

Thanks to our sponsors for this performance!

PROGRAM NOTES

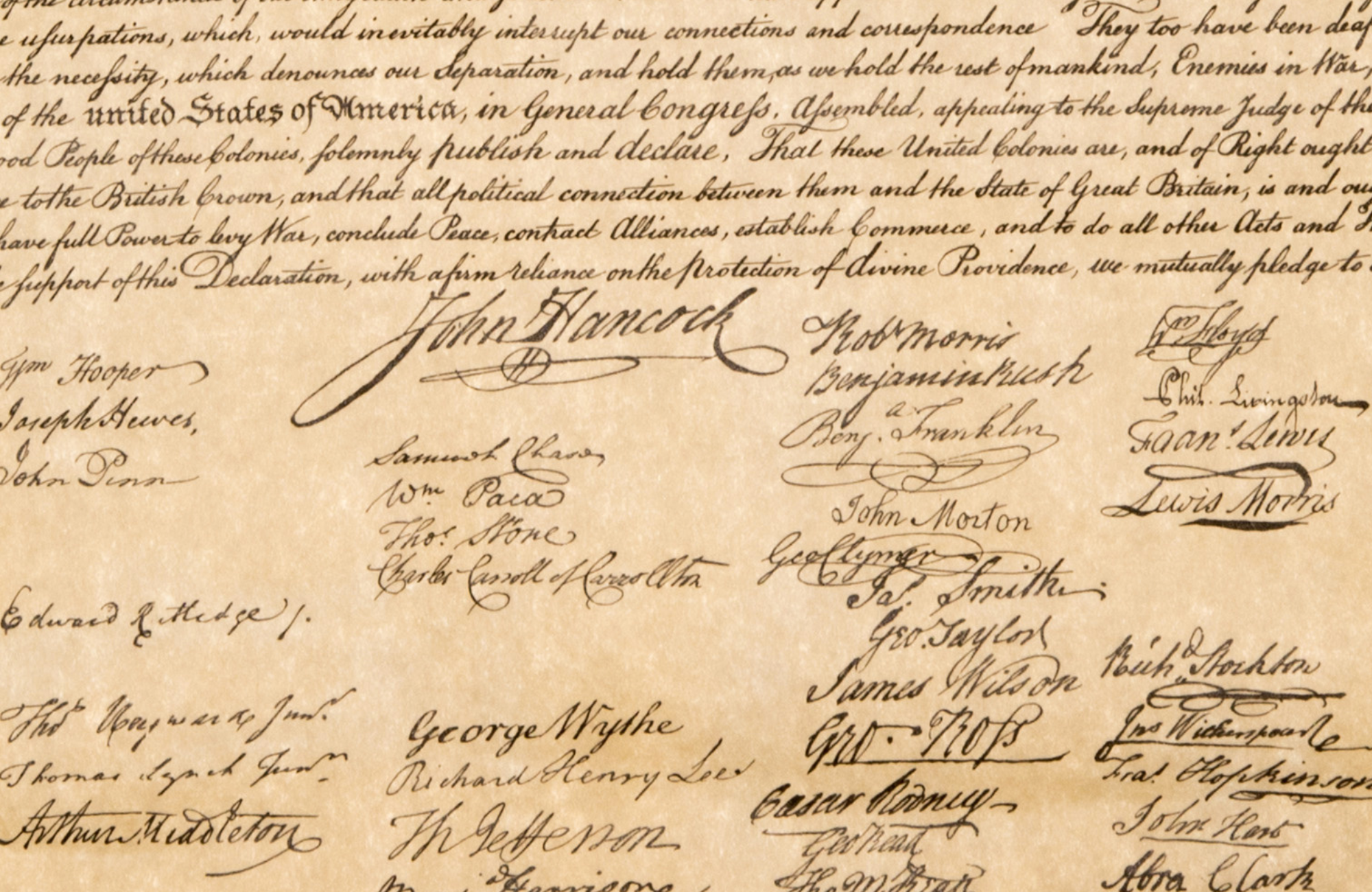

This afternoon’s concert is bracketed by two contemplative pieces—one looking backward, one looking toward the future. Our opener is Elegy: A Cry from the Grave (2015) by Carlos Simon (b. 1986), whose compositions have roots in a wide range of traditions, including classical, jazz, R&B, and gospel (he grew up playing the piano in the church where his father preached). His music is also stimulated by a concern for social justice. The work we’re presenting today, for instance, is “an artistic reflection dedicated to those who have been murdered wrongfully by an oppressive power”—in particular, Trayvon ...

This afternoon’s concert is bracketed by two contemplative pieces—one looking backward, one looking toward the future. Our opener is Elegy: A Cry from the Grave (2015) by Carlos Simon (b. 1986), whose compositions have roots in a wide range of traditions, including classical, jazz, R&B, and gospel (he grew up playing the piano in the church where his father preached). His music is also stimulated by a concern for social justice. The work we’re presenting today, for instance, is “an artistic reflection dedicated to those who have been murdered wrongfully by an oppressive power”—in particular, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner and Michael Brown. From the subtitle, you might expect something harsh and dissonant, marked by anger and resentment, like Shostakovich’s searing Eighth String Quartet, which was explicitly a response to the fire-bombing of Dresden and implicitly a response to his own experiences under Stalin. In fact, though, Simon’s brief, sorrowful work relies on what he calls “strong lyricism and a lush harmonic character.” And while it has touches of bitterness, this rumination on loss is also dotted—unlike the Shostakovich—with moments of hope. If you’ve been moved by our performances of Vaughan Williams’s Tallis Fantasia and Aaron Jay Kernis’s Elegy–For Those We Lost, you’ll find that this transcendent work speaks powerfully to you, too.

Our closing work may likewise defy expectations. Richard Wagner (1813–1883) wrote his Siegfried Idyll in 1870, when he was working on his four-opera cycle The Ring of the Nibelung, the most monumental work in the standard classical repertoire. He was, in addition, still living in the aftermath his Tristan und Isolde, whose radical harmonic practice shook music for decades to come. His personal life was similarly larger than life. At the time, he was living with his second wife, Cosima, at the epicenter of two generations of spectacular sexual scandals. Political storms were brewing, too.

Amidst all this sturm und drang, both musical and personal, Wagner surprised Cosima with an intimate greeting that was performed by a small orchestra from the stairwell to awaken her on Christmas day. It was intended to celebrate her birthday, but it was also (here’s the forward-looking part) a salutation to their new-born son Siegfried, who eventually carried on the family flame as composer, conductor, and impresario. The Siegfried Idyll is based largely on themes from Siegfried, the third of the Ring Operas—but they are recast in the gentlest way possible. Originally scored for thirteen players—five woodwinds, three brass, and string quintet—the Siegfried Idyll is nowadays usually performed with a larger string section.

In between these two works, we have two concertos that are more outgoing in spirit. First, before intermission, lutenist Michael Leopold joins us for the Concerto in D, written around 1730 by Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741). The concerto is one of Vivaldi’s most popular. These days, it is usually played on a guitar—and if that’s the way you know it, you may hear some illuminating differences this afternoon, when it’s played on a lute. Most obvious is the timbre of the instrument: The lute, Michael points out, has double strings, and gut strings at that—and it’s played with flesh of the finger. The guitar, with nylon strings, is usually played with finger nails—and strung with higher tension. Even though the higher tension means that the guitar is louder, the sound is rounder, too, so the lute is brighter. The tuning, Michael points out, is apt to be different, too: Unlike the steel frets on the guitar, the gut frets on the lute are moveable, allowing more control in the tuning of the instrument. This is especially important in playing early music, which was not written for the equal-tempered tuning—where each half-step is exactly the same—that’s the norm today.

More important, though, is the additional variety—and, consequently, the richer musical affect—you get on a lute when it’s played in a historically appropriate manner. In modern playing, says Michael, “You’re supposed to be able to have everything sound the same. For a guitarist, for instance, there should be no difference between playing with your thumb and playing with your ring finger. You’re striving for equality. All of your fingers are equally strong and balanced. But on a lute, your thumb and your middle finger are strong, your index and your ring fingers are weak. You try to use a strong finger on a strong beat, a weak finger on a weak beat.” Played with modern techniques, baroque music gets flattened out. Played with baroque technique, “Every note is a little bit different, nothing is the same. That is what really brings it to life and makes baroque music exciting and interesting. Every measure has a hierarchy. Musical architecture is clear.” As a result, the music has the same kind of richness and variety that you find in baroque visual art. This afternoon’s performances, played with reduced forces, should make that variety especially clear.

The Concerto is in three movements: a moderately quick allegro, a largo of remarkable beauty that may remind us of Vivaldi’s career as an opera composer, and a zippy finale with a strong dance flavor. All give the lutenist ample opportunity to show off the instrument’s (and the performer’s) special qualities. As a supplement, Michael will also be performing Vivaldi’s Trio Sonata in G Minor. This minor-key Trio is less vibrant: after a slightly mournful Andante, we get a profound slow movement, and a finale that ups the pace, even though it doesn’t provide a great deal of sunlight. It offers a striking contrast to the Concerto, and further reveals the instrument’s expressive capabilities—not to mention Vivaldi’s compositional range.

After intermission, we’re offering the first movement of the Piano Concerto No. 1 by Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847), composed in 1831 while he was in the afterglow of a visit to Italy. He was barely in his twenties at the time—and our piano soloist, Paul Di Folco, the winner of this year’s Civic Morning Musicals Concerto Contest, is even younger than that. Paul didn’t really know the concerto before he chose it for the contest. In fact—and this is but one sign of his adventurous spirit—he chose it from the repertoire list in part because it was something unfamiliar. As he’s learned it, he’s come to love it—as will you, if you don’t love it already.

The Concerto, says Paul, is “almost like a bridge between Classical age and Romantic age concertos.” Its forward-thinking quality is obvious from the start. Instead of beginning with a long orchestral introduction that presents the main thematic material, Mendelssohn gives us the briefest of announcements. Then “the piano enters immediately, and the Concerto just sweeps you off your feet.” It was written very quickly, Paul points out, which is evident not in any “structural deficiencies” (you wouldn’t expect that in Mendelssohn!), but in its spirit, which “is so vivacious and fiery the whole way through. It picks you up and doesn’t let you down throughout the whole duration.”

If you think of Mendelssohn as a well-behaved composer—a reasonable preconception, since he was adored by Queen Victoria and became the model for “Victorian” music—the energy of this piece may shock you. Paul describes it as “very passionate—in some places, white hot”—perhaps even angry. At the same time (and here’s its more Classical side), beneath the exuberance, the keyboard writing is characterized by extreme precision. “It fits the hand of a pianist so well, like a glove, the whole way through, which gives it ease of expression. When it comes to voicing things, it’s almost like Mozart. It’s so natural, it flows right off your fingers into the room, and carries the audience with it so well.” This precision has tremendous benefits for the performer: “Mendelssohn is comfortable to play, without fatigue,” says Paul. “And when it comes so easily to the fingers, it gives you more room to express yourself.” That’s a benefit for the listeners as well.

Peter J. Rabinowitz

Have any comments or questions? Please write to me at prabinowitz@ExperienceSymphoria.org

FEATURED ARTISTS

Described as bringing an “artisan storyteller’s sensitivity… shaping passages with clarity and power via beautifully sculpted dynamics… revealing orchestral character not seen or heard before” (Arts Knoxville) Lawrence Loh enjoys a dynamic career as a conductor of orchestras all over the world.

After an extensive two ...

Described as bringing an “artisan storyteller’s sensitivity… shaping passages with clarity and power via beautifully sculpted dynamics… revealing orchestral character not seen or heard before” (Arts Knoxville) Lawrence Loh enjoys a dynamic career as a conductor of orchestras all over the world.

After an extensive two year search, Lawrence Loh was recently named Music Director of the Waco Symphony Orchestra beginning in the Spring of 2024. Since 2015, he has served as Music Director of The Syracuse Orchestra (formerly called Symphoria), the successor to the Syracuse Symphony Orchestra. “The connection between the organization and its audience is one of the qualities that’s come to define Syracuse’s symphony as it wraps up its 10th season, a milestone that might have seemed impossible at the beginning,” (Syracuse.com) The Syracuse Orchestra and Lawrence Loh show that it is possible to create a “new, more sustainable artistic institution from the ground up.”

Appointed Assistant Conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony in 2005, Mr Loh was quickly promoted to Associate and Resident Conductor within the first three years of working with the PSO. Always a favorite among Pittsburgh audiences, Loh returns frequently to his adopted city to conduct the PSO in a variety of concerts. Mr. Loh previously served as Music Director of the West Virginia Symphony Orchestra, Music Director of the Northeastern Pennsylvania Philharmonic, Artistic Director and Principal Conductor of the Syracuse Opera, Music Director of the Pittsburgh Youth Symphony Orchestra, Associate Conductor of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, Associate Conductor of the Colorado Symphony Orchestra and Music Director of the Denver Young Artists Orchestra.

Mr. Loh’s recent guest conducting engagements include the San Francisco Symphony, Dallas Symphony, North Carolina Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, Sarasota Orchestra, Florida Orchestra, Pensacola Symphony, Atlanta Symphony, National Symphony, Detroit Symphony, San Diego Symphony, Seattle Symphony, National Symphony (D.C.), Utah Symphony, Rochester Philharmonic, Indianapolis Symphony, Calgary Philharmonic, Buffalo Philharmonic, Albany Symphony and the Cathedral Choral Society at the Washington National Cathedral. His summer appearances include the festivals of Grant Park, Boston University Tanglewood Institute, Tanglewood with the Boston Pops, Chautauqua, Sun Valley, Shippensburg, Bravo Vail Valley, the Kinhaven Music School and the Performing Arts Institute (PA).

As a self-described “Star Wars geek” and film music enthusiast, Loh has conducted numerous sold-out John Williams and film music tribute concerts. Part of his appeal is his ability to serve as both host and conductor. “It is his enthusiasm for Williams’ music and the films for which it was written that is Loh’s great strength in this program. A fan’s enthusiasm drives his performances in broad strokes and details and fills his speaking to the audience with irresistible appeal. He used no cue cards. One felt he could speak at filibuster length on Williams’ music.” (Pittsburgh Tribune)

Mr Loh has assisted John Williams on multiple occasions and has worked with a wide range of pops artists from Chris Botti and Ann Hampton Callaway to Jason Alexander and Idina Menzel. As one of the most requested conductors for conducting Films in Concert, Loh has led Black Panther, Star Wars (Episodes 4-6), Jaws, Nightmare Before Christmas, Jurassic Park, Casablanca, The Wizard of Oz and Singin’ in the Rain, among other film productions.

Lawrence Loh received his Artist Diploma in Orchestral Conducting from Yale, his Masters in Choral Conducting from Indiana University and his Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Lawrence Loh was born in southern California of Korean parentage and raised in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He and his wife Jennifer have a son, Charlie, and a daughter, Hilary. Follow him on instagram @conductorlarryloh or Facebook at @lawrencelohconductor or visit his website, www.lawrenceloh.com

Michael Leopold holds both an undergraduate degree in music and a master’s degree in historical plucked instruments from American Universities as well as a degree in lute and theorbo from L’Istituto di Musica Antica of the Accademia Internazionale della Musica in Milan, Italy. Originally from Northern California ...

Michael Leopold holds both an undergraduate degree in music and a master’s degree in historical plucked instruments from American Universities as well as a degree in lute and theorbo from L’Istituto di Musica Antica of the Accademia Internazionale della Musica in Milan, Italy. Originally from Northern California and after living in Milan, Italy for 16 years and Canada for 5 years, he now resides in the United States. He has performed both as a soloist and as an accompanist throughout Europe, Australia, Japan, South America, Mexico, Canada and the United States.

Michael has played with a number of leading Italian early music groups, including Concerto Italiano, La Risonanza, La Venexiana and La Pietà de’ Turchini and several American period-instrument ensembles. He has also collaborated with several orchestras and opera companies, including Orchestra Verdi di Milano, Opera Australia, San Francisco Opera, Barcelona Opera, Los Angeles Opera, Houston Grand Opera, Washington National Opera, Glimmerglass Opera, Chicago Opera Theater, Gulbenkian Mùsica, Houston Symphony, Minnesota Orchestra, Nashville Symphony, Cincinnati Opera and Portland Opera. His performances in operas have been noted in various reviews, “Michael Leopold was a standout on theorbo, providing some of the most sensitive and heartfelt musical moments of the evening,” (Kathryn Bacasmot, Chicago Classical Music 1 May 2012.Teseo, Chicago Opera Theater) and “High marks especially to the marvelous theorbo, lute and baroque guitar specialist, Michael Leopold, whose recitatives added dazzling color.” (Harvey Steiman, Seen and Heard International 7 November 2011. Xerxes, San Francisco Opera).He can be heard in recordings on the Stradivarius, Glossa, Naïve, Linn, Avie, Centaur and Naxos labels.

Paul Di Folco is a senior at Manlius Pebble Hill School. His pianistic accomplishments include participation in the 2022 Forte/Piano Summer Academy at the Cornell-Westfield Center for Historical Keyboards, four-time participation in the Ithaca College Summer Piano Institute, 2022 Claudette Sorel Fellow, 1st prize in the 2023 Civic Morning Musicals Youth ...

Paul Di Folco is a senior at Manlius Pebble Hill School. His pianistic accomplishments include participation in the 2022 Forte/Piano Summer Academy at the Cornell-Westfield Center for Historical Keyboards, four-time participation in the Ithaca College Summer Piano Institute, 2022 Claudette Sorel Fellow, 1st prize in the 2023 Civic Morning Musicals Youth Concerto Competition, and a live performance of the Goldberg Variations in 2021. Paul also plays the viola for his school orchestra and has participated in NYSSMA and regional festivals several times.