We begin with Bernstein’s Candide Overture, a buoyant and lively curtain-raiser, and close the show with symphonic dances from West Side Story. 2019 National Sphinx Competition winner Sterling Elliott plays Schumann’s Concerto for Cello.

PROGRAM

BERNSTEIN: Candide Overture ![]()

SCHUMANN: Concerto for Cello in A minor, Op. 129 ![]()

ANNA CLYNE: This Midnight Hour ![]()

BERNSTEIN: West Side Story: Symphonic Dances ![]()

Thanks to our sponsors for this performance!

Thank you to our media sponsor!

PROGRAM NOTES

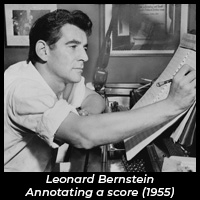

Although we didn’t know it when we scheduled this concert anchored in the art of Leonard Bernstein (1918–1990), our choice of timing turns out to be have been auspicious: Bradley Cooper’s new film about Bernstein’s marriage to Felicia Montealegre, Maestro, is scheduled to be released in the United States on November 22.

The program catches Bernstein at a high point in his career. Candide (1956) and West Side Story (1957) opened within less than a year of each other—and they confirmed ...

Although we didn’t know it when we scheduled this concert anchored in the art of Leonard Bernstein (1918–1990), our choice of timing turns out to be have been auspicious: Bradley Cooper’s new film about Bernstein’s marriage to Felicia Montealegre, Maestro, is scheduled to be released in the United States on November 22.

The program catches Bernstein at a high point in his career. Candide (1956) and West Side Story (1957) opened within less than a year of each other—and they confirmed the 38-year-old Leonard Bernstein as our most protean musician. It’s not simply that he was already a world-famous conductor (he had made his New York Philharmonic debut in his early twenties and was appointed co-principal conductor in 1957) and a startlingly good concert pianist. After all, lots of conductors launched their careers early, and many were also first-rate instrumentalists. Nor was it simply that he wrote music as well. So did many of the other great conductors (including, of course, his idol Gustav Mahler). No, what distinguished Bernstein was the astonishing range of his sympathies, in terms of both genre and mood.

He’d already written symphonic music, popular musicals like On the Town (source of the song “New York, New York”), ballets, and even a blues song, “Big Stuff,” for Billie Holiday. He was equally at home in radiant music evoking innocent love and in rough music bristling with working class grit (his film score for On the Waterfront). What made Candide and West Side Story stand out in particular was the skill with which he managed to combine all those different voices into works that were staggering in their variety, yet simultaneously consistent in their vision—works in which high-toned classical procedures (for instance, the fugue in West Side Story’s “Cool”) rubbed up against vernacular idioms.

He’d already written symphonic music, popular musicals like On the Town (source of the song “New York, New York”), ballets, and even a blues song, “Big Stuff,” for Billie Holiday. He was equally at home in radiant music evoking innocent love and in rough music bristling with working class grit (his film score for On the Waterfront). What made Candide and West Side Story stand out in particular was the skill with which he managed to combine all those different voices into works that were staggering in their variety, yet simultaneously consistent in their vision—works in which high-toned classical procedures (for instance, the fugue in West Side Story’s “Cool”) rubbed up against vernacular idioms.

Besides their eclecticism, Candide and West Side Story had another quality in common: Both were politically committed. Candide was based on Voltaire’s novel from 1659, a bitterly satiric attack on a wide range of social ills that still plague the world more than 350 years later. West Side Story, based on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, was less satiric, more direct—but it was no less bitter in its depiction of racial and ethnic violence, and (more important still) in its searing indictment of the ways in which the powers-that-be use (and even encourage) that animosity for their own ends.

The spirit of their literary sources certainly helped fuel the spirit of the two works. At the same time, though, Bernstein and his collaborators (including writers Lillian Hellman and the young Stephen Sondheim) drew on a rich tradition of eclectic, socially engaged musical theater that, in the mid-20th century, included such works as the Kern/Hammerstein Show Boat, Marc Blitzstein’s The Cradle will Rock (a work Bernstein conducted), and especially the Blitzstein version of Weill and Brecht’s Threepenny Opera (a work that Bernstein also conducted and that was still in the middle of its unprecedented five-year off-Broadway run when Candide and West Side Story opened). Add to this the sheer genius of the creators, and both “musicals” took this tradition to new heights—and radically influenced the history of musical theater.

I put the term “musicals” in quotation marks because, in a sense, they reformulated the conventions of the genre. Candide may have opened on Broadway as a musical, but Bernstein titled it a “comic operetta” (a slippery term), and in fact, it has had (like Threepenny) tremendous success in opera houses around the world. The work has been subject to numerous revisions over the years, with changes in its orchestration, in its libretto, and even in what songs are included, who sings them, and what order appear in. It sometimes seems as if no two productions are musically identical. But whatever version you hear, it always begins with the bubbly, Rossini-esque Overture: a “playful” introduction, in the words of conductor Larry Loh. It was the first Bernstein work that Larry ever conducted—indeed, while at Aspen, he cajoled a group of friends to form an orchestra just so he could perform it. His enthusiasm is not hard to understand: The Overture to Candide is so widely beloved, in fact, that it has probably become the most popular 20th-century overture on classical concerts.

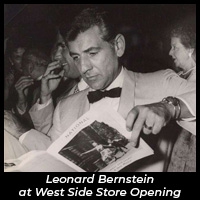

West Side Story has been successful in the opera house, too—as well, of course, as in two wildly popular screen versions. In the concert hall, it’s usually represented by the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story, which was compiled in 1960. The title is significant. West Side Story is, as the score puts it, “based on a conception of Jerome Robbins.” Robbins, a Balanchine protégé, was, among other things, a dancer and choreographer who shared Bernstein’s range, working in classical ballet, Broadway, and film. He had already collaborated with Bernstein on several works, including the ballets Facsimile and Fancy Free—and dance was always integral to the conception of West Side Story.

West Side Story has been successful in the opera house, too—as well, of course, as in two wildly popular screen versions. In the concert hall, it’s usually represented by the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story, which was compiled in 1960. The title is significant. West Side Story is, as the score puts it, “based on a conception of Jerome Robbins.” Robbins, a Balanchine protégé, was, among other things, a dancer and choreographer who shared Bernstein’s range, working in classical ballet, Broadway, and film. He had already collaborated with Bernstein on several works, including the ballets Facsimile and Fancy Free—and dance was always integral to the conception of West Side Story.

That dance element dominates the Symphonic Dances, which, as Larry points out, sidesteps many of the show’s most popular songs. Still, for all the youthful kinetic energy of the score, it ends—as the show ends—soberly. In Romeo and Juliet, of course, both main characters die; in West Side Story, Maria remains after the death of her brother and her lover, offering a possibility of hope for the future. It’s an ambiguous possibility, however—the heartbreaking final measures, perhaps modeled on Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra, leave us up in the air.

Anna Clyne (b. 1980) may not have been directly influenced by Bernstein, but she shares some of his musical sensibility. Her brilliantly orchestrated tone poem This Midnight Hour (2015) merges ferocity and rapture in a way that may bring West Side Story to mind; and it certainly reveals the eclectic resistance to stylistic constraints that we hear in both Bernstein scores. Then, too, like the Bernstein works, it has a literary foundation, having been inspired by two poems. One is a three-line snapshot by Juan Ramón Jiménez that describes music, in Robert Bly’s translation, as “a naked woman running mad through the pure night”; the other is the opening of Charles Baudelaire’s troubling “Harmonie du soir” (see Appendix).

Anna Clyne (b. 1980) may not have been directly influenced by Bernstein, but she shares some of his musical sensibility. Her brilliantly orchestrated tone poem This Midnight Hour (2015) merges ferocity and rapture in a way that may bring West Side Story to mind; and it certainly reveals the eclectic resistance to stylistic constraints that we hear in both Bernstein scores. Then, too, like the Bernstein works, it has a literary foundation, having been inspired by two poems. One is a three-line snapshot by Juan Ramón Jiménez that describes music, in Robert Bly’s translation, as “a naked woman running mad through the pure night”; the other is the opening of Charles Baudelaire’s troubling “Harmonie du soir” (see Appendix).

The resulting work we might well be called “cinematic”—in several ways. As Larry points out, the macabre opening sets a cinematic mood; and although it’s not entirely soaked with the lush Hollywood sound we get from blockbusters scored by Korngold and John Williams (although there is a bit of that here), it does engage in rapid cutting among different moods. The piece is only 14 minutes or so long, but from the opening, marked “Ferocious with drive” to the final measure marked “Aggressive,” Clyne shifts emotional landscape more than twenty times, interleaving the “Feverish” with the “Regal,” alternating the “Soaring and Passionate” with the “Skittish.” There are some folk inflections, too; and toward the middle, rhythmically driving music collides against what the composer called a “Parisian-esque waltz,” with half the violas playing a quarter-step off from their colleagues to help imitate the sound of an accordion. Clyne hopes that the music will “evoke a visual journey”—and there’s no doubt that it provides an uneasy but thrilling sense of adventure.

The 1850 Cello Concerto by Robert Schumann (1810–1856) is an ideal complement to Bernstein and Clyne, for two reasons. First, Bernstein was a devoted advocate of Schumann’s music, especially of the Cello Concerto, which he performed often and recorded with four different cellists in the course of his career. Second, the work provides a needed contrast to its hyperkinetic companions. Written late in the composer’s life, it’s an inward, slightly melancholy piece, largely without exhibitionist flash (although still extremely difficult to play) until the finale. Indeed, it’s so restrained that while his wife Clara Schumann loved it from the beginning, it took a while for it to catch on more widely. Even as late as the middle of the 20th century, cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was sufficiently frustrated with the sound of the orchestration that he had his friend Shostakovich re-orchestrate it for him, although he eventually came around to the original version.

The 1850 Cello Concerto by Robert Schumann (1810–1856) is an ideal complement to Bernstein and Clyne, for two reasons. First, Bernstein was a devoted advocate of Schumann’s music, especially of the Cello Concerto, which he performed often and recorded with four different cellists in the course of his career. Second, the work provides a needed contrast to its hyperkinetic companions. Written late in the composer’s life, it’s an inward, slightly melancholy piece, largely without exhibitionist flash (although still extremely difficult to play) until the finale. Indeed, it’s so restrained that while his wife Clara Schumann loved it from the beginning, it took a while for it to catch on more widely. Even as late as the middle of the 20th century, cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was sufficiently frustrated with the sound of the orchestration that he had his friend Shostakovich re-orchestrate it for him, although he eventually came around to the original version.

In form (although not in spirit), the Concerto is reminiscent of the Violin Concerto by the Schumanns’ good friend Mendelssohn, which we heard at our first Masterworks this year. It’s in three linked movements, tightly unified in its thematic content; and perhaps taking a cue from Clara’s Piano Concerto (which we presented last year), Robert showcases the orchestra’s principal cellist, who has a major role in the second movement.

Heard on its own, it would be easy to see the Concerto as a reflection of, even submission to, the encroaching syphilis-caused mental illness that clouded his final years. But as I’ve said often, there’s no easy connection between composers’ biographical situations and their music—and by all accounts, this was a relatively happy period in his life. He composed it, astonishingly, within a two-week burst of energy in 1850—and a week later, he was at work on his Symphony No. 3, one of his most life-affirming works. Then, too, in his final days of lucidity, before his suicide attempt and his decision to enter a sanatorium, he found the act of correcting proofs for the piece a source of solace. No surprise: as Clara recognized, it’s a work of tremendous beauty and strength.

And don’t forget: more music by Robert Schumann—his Symphony No. 1 (“Spring”)— will be featured on our first Casual Concert, on Sunday afternoon, November 12, at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Peter J. Rabinowitz

Have any comments or questions? Please write to me at prabinowitz@ExperienceSymphoria.org

APPENDIX

Harmonie du soir – by Charles Baudelaire

Voici venir les temps où vibrant sur sa tige

Chaque fleur s’évapore ainsi qu’un encensoir;

Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir;

Valse mélancolique et langoureux vertige!

Chaque fleur s’évapore ainsi qu’un encensoir;

Le violon frémit comme un coeur qu’on afflige;

Valse mélancolique et langoureux vertige!

Le ciel est triste et beau comme un grand reposoir.

Le violon frémit comme un coeur qu’on afflige,

Un coeur tendre, qui hait le néant vaste et noir!

Le ciel est triste et beau comme un grand reposoir;

Le soleil s’est noyé dans son sang qui se fige.

Un coeur tendre, qui hait le néant vaste et noir,

Du passé lumineux recueille tout vestige!

Le soleil s’est noyé dans son sang qui se fige…

Ton souvenir en moi luit comme un ostensoir!

Harmonie du soir

translated by William Aggeler:

The season is at hand when swaying on its stem

Every flower exhales perfume like a censer;

Sounds and perfumes turn in the evening air;

Melancholy waltz and languid vertigo!

Every flower exhales perfume like a censer;

The violin quivers like a tormented heart;

Melancholy waltz and languid vertigo!

The sky is sad and beautiful like an immense altar.

The violin quivers like a tormented heart,

A tender heart, that hates the vast, black void!

The sky is sad and beautiful like an immense altar;

The sun has drowned in his blood which congeals…

A tender heart that hates the vast, black void

Gathers up every shred of the luminous past!

The sun has drowned in his blood which congeals…

Your memory in me glitters like a monstrance!

FEATURED ARTISTS

Acclaimed for his stellar stage presence and joyous musicianship, cellist Sterling Elliott is a 2021 Avery Fisher Career Grant recipient and the winner of the Senior Division of the 2019 National Sphinx Competition. Already in his young career, he has appeared with major orchestras such as the Philadelphia Orchestra, the New ...

Acclaimed for his stellar stage presence and joyous musicianship, cellist Sterling Elliott is a 2021 Avery Fisher Career Grant recipient and the winner of the Senior Division of the 2019 National Sphinx Competition. Already in his young career, he has appeared with major orchestras such as the Philadelphia Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, the Boston Symphony, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Detroit Symphony and the Dallas Symphony, with noted conductors Yannick Nezet-Seguin, Thomas Wilkins, Jeffrey Kahane, Mei Ann Chen and others.

This season, Elliott debuts with the Minnesota Orchestra, Grand Rapids Symphony, Charlotte Symphony, Pacific Symphony, San Antonio Symphony and New Jersey Symphony. He also performs the world premiere of a new orchestral version of John Corigliano’s Phantasmagoria, commissioned for him by a consortium of orchestras including the Orlando Philharmonic and music director Eric Jacobsen. He makes his UK recital debut at Wigmore Hall in February.

The 2022-2023 season saw his debuts at the Aspen Music Festival, performing the Brahms Double Concerto with Gil Shaham, as well as with the Colorado Symphony, Cincinnati Symphony, North Carolina Symphony and Ft. Worth Symphony, among others. He appeared in recital under the auspices of the San Francisco Symphony, the New York Philharmonic, Shriver Hall in Baltimore, the Tippett Rise Festival and Capitol Region Classical in Albany, NY.

Fast becoming a favorite on the summer festival circuit, Sterling has appeared at Music@Menlo, Chamberfest in Cleveland and Chamberfest Northwest in Calgary, Music at Angel Fire and the La Jolla Music Society. In Summer 2023, he made his orchestral debut with the San Francisco Symphony; performed chamber music with Nicola Benedetti, Stefan Jackiw and others at the Edinburgh Festival; and made a return appearance at the Hollywood Bowl with the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Sterling Elliott participates in several programs alongside exceptionally talented young artists. In April 2023, he was selected by The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center for its Bowers Program, a three-year residency. As a Bowers Program artist, he will perform in CMS tours nationally, and play subscription concerts at Alice Tully Hall. In June 2023, the London-based Young Classical Artists Trust named him their YCAT–Music Masters Robey Artist, a two-year program during which YCAT will provide UK booking and management and Sterling will fulfill an ambassadorial role, leading workshops and engaging with young learners in schools across London to inspire and enhance their musical education. In Spring 2022, Sterling participated in Performance Today’s Young Artist Residency, which featured educational events, interviews and a feature on the nationally syndicated radio program.

Sterling has a long history with the Sphinx Organization where he won the 2014 Junior Division Competition, becoming the first alumnus from the Sphinx Performance Academy to win the Sphinx Competition. The following year he went on to tour with the Sphinx Virtuosi before being awarded the Organization’s Isaac Stern Award in 2016. This season, Sterling will receive a Sphinx Medal of Excellence, the highest honor bestowed by the Sphinx Organization, awarded to artists who, early in their career, demonstrate artistic excellence, outstanding work ethic, a spirit of determination, and an ongoing commitment to leadership and their communities.

Born into a musical household, Sterling initially wanted to play the violin like his older brother and sister. After a bit of encouragement, he completed The Elliott Family String Quartet, an ensemble that enjoyed personalized arrangements of genres such as bluegrass, gospel, and funk music.

Sterling is pursuing an Artist Diploma at the Juilliard School under the tutelage of Joel Krosnick and Clara Kim, following completion of his Master of Music and undergraduate degrees at Juilliard. He is an ambassador of the Young Strings of America, a string sponsorship operated by Shar Music. He performs on a 1741 Gennaro Gagliano cello on loan through the Robert F. Smith Fine String Patron Program, in partnership with the Sphinx Organization.

Described as bringing an “artisan storyteller’s sensitivity… shaping passages with clarity and power via beautifully sculpted dynamics… revealing orchestral character not seen or heard before” (Arts Knoxville) Lawrence Loh enjoys a dynamic career as a conductor of orchestras all over the world.

After an extensive two ...

Described as bringing an “artisan storyteller’s sensitivity… shaping passages with clarity and power via beautifully sculpted dynamics… revealing orchestral character not seen or heard before” (Arts Knoxville) Lawrence Loh enjoys a dynamic career as a conductor of orchestras all over the world.

After an extensive two year search, Lawrence Loh was recently named Music Director of the Waco Symphony Orchestra beginning in the Spring of 2024. Since 2015, he has served as Music Director of The Syracuse Orchestra (formerly called Symphoria), the successor to the Syracuse Symphony Orchestra. “The connection between the organization and its audience is one of the qualities that’s come to define Syracuse’s symphony as it wraps up its 10th season, a milestone that might have seemed impossible at the beginning,” (Syracuse.com) The Syracuse Orchestra and Lawrence Loh show that it is possible to create a “new, more sustainable artistic institution from the ground up.”

Appointed Assistant Conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony in 2005, Mr Loh was quickly promoted to Associate and Resident Conductor within the first three years of working with the PSO. Always a favorite among Pittsburgh audiences, Loh returns frequently to his adopted city to conduct the PSO in a variety of concerts. Mr. Loh previously served as Music Director of the West Virginia Symphony Orchestra, Music Director of the Northeastern Pennsylvania Philharmonic, Artistic Director and Principal Conductor of the Syracuse Opera, Music Director of the Pittsburgh Youth Symphony Orchestra, Associate Conductor of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, Associate Conductor of the Colorado Symphony Orchestra and Music Director of the Denver Young Artists Orchestra.

Mr. Loh’s recent guest conducting engagements include the San Francisco Symphony, Dallas Symphony, North Carolina Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, Sarasota Orchestra, Florida Orchestra, Pensacola Symphony, Atlanta Symphony, National Symphony, Detroit Symphony, San Diego Symphony, Seattle Symphony, National Symphony (D.C.), Utah Symphony, Rochester Philharmonic, Indianapolis Symphony, Calgary Philharmonic, Buffalo Philharmonic, Albany Symphony and the Cathedral Choral Society at the Washington National Cathedral. His summer appearances include the festivals of Grant Park, Boston University Tanglewood Institute, Tanglewood with the Boston Pops, Chautauqua, Sun Valley, Shippensburg, Bravo Vail Valley, the Kinhaven Music School and the Performing Arts Institute (PA).

As a self-described “Star Wars geek” and film music enthusiast, Loh has conducted numerous sold-out John Williams and film music tribute concerts. Part of his appeal is his ability to serve as both host and conductor. “It is his enthusiasm for Williams’ music and the films for which it was written that is Loh’s great strength in this program. A fan’s enthusiasm drives his performances in broad strokes and details and fills his speaking to the audience with irresistible appeal. He used no cue cards. One felt he could speak at filibuster length on Williams’ music.” (Pittsburgh Tribune)

Mr Loh has assisted John Williams on multiple occasions and has worked with a wide range of pops artists from Chris Botti and Ann Hampton Callaway to Jason Alexander and Idina Menzel. As one of the most requested conductors for conducting Films in Concert, Loh has led Black Panther, Star Wars (Episodes 4-6), Jaws, Nightmare Before Christmas, Jurassic Park, Casablanca, The Wizard of Oz and Singin’ in the Rain, among other film productions.

Lawrence Loh received his Artist Diploma in Orchestral Conducting from Yale, his Masters in Choral Conducting from Indiana University and his Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Lawrence Loh was born in southern California of Korean parentage and raised in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He and his wife Jennifer have a son, Charlie, and a daughter, Hilary. Follow him on instagram @conductorlarryloh or Facebook at @lawrencelohconductor or visit his website, www.lawrenceloh.com