2021 Gramophone Artist of the Year James Ehnes, one of the most sought-after violinists on the international stage, joins us in the first half, followed by Ravel’s orchestral adaptation of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition.

NEW THIS SEASON! Symphoria has made special arrangements for pre-paid parking at the Equitable Towers Parking Garage, just steps away from the Crouse-Hinds Theater, conveniently located across Montgomery Street (entrance is directly across from the War Memorial). To purchase pre-paid concert parking, simply click the “Buy Now” button and select “September, 30, 2023 PARKING.” To enhance your confidence at being downtown, Symphoria ambassadors will be stationed between Oncenter Crouse Hinds Theater and the garage entrance on Montgomery Street before and after concerts.

PROGRAM

SMITH: The Star-Spangled Banner ![]()

ENESCU: Romanian Rhapsody, Op. 11, No. 1, A major ![]()

MENDELSSOHN: Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 ![]()

MUSSORGSKY/RAVEL: Pictures at an Exhibition ![]()

Thanks to our sponsors for this performance!

Jim & Marilyn Seago

Thanks to our Media Sponsor

PROGRAM NOTES

Mozart is generally the poster child for classical-music prodigies. But while his early development was exceptional, it was not unique: The first half of tonight’s concert offers works by two composers who shared his astonishing early fluency.

George Enescu (1881–1955) started playing the violin at the age of four and began composing a year later; he enrolled in the Vienna Conservatory at the age of seven. He soon blossomed into a wide-ranging musician, achieving success as a world-class violinist and conductor (he was considered as a replacement when Toscanini stepped down from the ...

Mozart is generally the poster child for classical-music prodigies. But while his early development was exceptional, it was not unique: The first half of tonight’s concert offers works by two composers who shared his astonishing early fluency.

George Enescu (1881–1955) started playing the violin at the age of four and began composing a year later; he enrolled in the Vienna Conservatory at the age of seven. He soon blossomed into a wide-ranging musician, achieving success as a world-class violinist and conductor (he was considered as a replacement when Toscanini stepped down from the New York Philharmonic). In both capacities, he championed the music of Bach. He’s best remembered, though, as Romania’s most important composer.

Enescu developed a distinctive style, rich in texture, seductive in melody, and resourceful in color, producing music that merged scrupulous attention to detail with the illusion of improvisatory sweep. It was rooted in a wide range of sources, from the baroque (Bach in particular) to late romanticism (Fauré was one of his teachers) and beyond. But perhaps the most profound influence on Enescu’s works was folk music. In his later works, the folk influence was distilled and personalized, as it was in the contemporary music of Bartók and Szymanowski. In contrast, his early Romanian Rhapsody No. 1 (1900) is a rollicking crowd-pleaser modeled on Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies and, as conductor Larry Loh suggests, the dance music of the Strauss dynasty. Here, the reliance on pre-existing tunes is far more direct, even if we can’t identify them.

Enescu developed a distinctive style, rich in texture, seductive in melody, and resourceful in color, producing music that merged scrupulous attention to detail with the illusion of improvisatory sweep. It was rooted in a wide range of sources, from the baroque (Bach in particular) to late romanticism (Fauré was one of his teachers) and beyond. But perhaps the most profound influence on Enescu’s works was folk music. In his later works, the folk influence was distilled and personalized, as it was in the contemporary music of Bartók and Szymanowski. In contrast, his early Romanian Rhapsody No. 1 (1900) is a rollicking crowd-pleaser modeled on Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies and, as conductor Larry Loh suggests, the dance music of the Strauss dynasty. Here, the reliance on pre-existing tunes is far more direct, even if we can’t identify them.

It’s a cliché to say that the Romanian Rhapsodies are Enescu’s most popular works—and indeed, they once were, sufficiently so that the composer resented the way they eclipsed his more mature works. Nowadays, things have changed—the later music (especially the chamber music) has increasingly come to represent Enescu, especially on recordings. In fact, this will be the first time that Larry has conducted the Romanian Rhapsody No. 1. As it has ceased to be overplayed, the work has gained a freshness lost in its heyday—and Larry and the orchestra are excited to have this chance to share it with us.

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847), too, was an extraordinary prodigy. Like Enescu, he achieved fame as a stellar instrumentalist: When Clara Schumann was unable to perform due to illness, Mendelssohn stepped in and sight-read the first performance of Robert Schumann’s immensely difficult Piano Quintet. He was also a conductor, and he shared Enescu’s devotion to Bach. His performance of the St. Matthew Passion, in fact, was largely responsible for the Bach revival that has continued to this day. And he too is best remembered as a composer who started early: His vital string symphonies were composed in his early teens, and he had written two mature masterpieces (his Octet and his Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture) before he turned twenty. Unlike Enescu, though, he found his voice early and didn’t change dramatically as he grew older. His Violin Concerto was completed in 1844, just a few years before his early death; but it’s clearly written by the same composer who wrote the earlier masterpieces.

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847), too, was an extraordinary prodigy. Like Enescu, he achieved fame as a stellar instrumentalist: When Clara Schumann was unable to perform due to illness, Mendelssohn stepped in and sight-read the first performance of Robert Schumann’s immensely difficult Piano Quintet. He was also a conductor, and he shared Enescu’s devotion to Bach. His performance of the St. Matthew Passion, in fact, was largely responsible for the Bach revival that has continued to this day. And he too is best remembered as a composer who started early: His vital string symphonies were composed in his early teens, and he had written two mature masterpieces (his Octet and his Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture) before he turned twenty. Unlike Enescu, though, he found his voice early and didn’t change dramatically as he grew older. His Violin Concerto was completed in 1844, just a few years before his early death; but it’s clearly written by the same composer who wrote the earlier masterpieces.

On the surface, there’s little in common between the Romanian Rhapsody No. 1 and the Mendelssohn Concerto. Where the Enescu is rough-hewn, rhythmically exuberant, and dance-infused with a strong rural flavor, the Mendelssohn is suave and urbane; where the Enescu flaunts the orchestra’s capabilities, the Mendelssohn (despite the characteristically luminous orchestration) treats the orchestra as secondary, with the soloist taking the spotlight; and where the Enescu is firmly rooted in tradition, the Mendelssohn, as tonight’s soloist James Ehnes reminds us, is revolutionary. “We forget,” he says, “how weird it is that the violin comes in almost immediately with this main theme, You’re right in the middle of this incredibly turbulent and passionate music from the very start.” He also points to the continuity of the three movements: “The bit between the second and third movements: No one can decide whether it’s part of the third moment or part of the second.”

Yet despite its departure from the conventions of its time, the Mendelssohn is not a provocative piece. Like the Enescu, it has an immediate communicative power—or, as James puts it, an “evergreen” quality. Indeed, he says, “If I had to play a piece every day, I would want it to be the Mendelssohn. It’s not about the quantity of love I feel for it—I don’t love it more than the Beethoven or the Brahms. Rather, in its nature, the Mendelssohn is always so fresh, so incredibly honest. Violinistically speaking, it’s always interesting: I can return to it over and over and over and always find joy and inspiration.”

So what can we expect tonight? James is not one of those performers who self-consciously aims to “do something that has never been done before.” His goal is not to surprise us, but rather, he says, to “play the way that I believe in, the way I feel Mendelssohn asks me to.” And yet, paradoxically, what we’ll experience tonight is unpredictable, for two reasons—reasons that have more to do with us, as audience, than with James.

First, James argues, our individual experiences of listening depend on our “frames of reference”—we each come with a different background, a different set of expectations. “So the only thing you can do as a performer is to be convinced of yourself: That’s going to affect each listener in a different way.” That’s part of “the fun of it.”

In addition, James’s local interpretive decisions in a given performance depend on the audience’s reactions as he plays: “I can’t tell you in advance how I’m going to read the room. I might need to shift in a certain way, depending how things are going and how I feel. There are times in a live performance where you might feel you need to shock the audience into attention. Or you might feel that they are so rapt that you can afford to bring everybody into you by playing very, very, very softly. You can’t anticipate that.” That, too, is part of “the fun of it.”

Modest Mussorgsky (1839-1881) also showed early talent, but nothing like the precocity of Enescu and Mendelssohn. And once he reached his maturity, he was burdened with a reputation as an artist who, despite his imagination, was deficient in terms of craft—a criticism never leveled at Enescu or Mendelssohn. Even Rimsky-Korsakov, one of his greatest advocates, referred to his “utter technical impotence.” Mussorgsky’s colleagues thus thought the best way to support his work was to refine it—and for years after his death, his music was heard primarily in editions that cleaned up his supposed faults. Only later did his nonconformity come to be appreciated (especially, at first, in France) as ingenuity rather than error. Nowadays, you’re far more likely to hear Mussorgsky’s own rough voice, rather than Rimsky-Korsakov’s splashier and more cultivated voice, when you listen to his opera Boris Godunov (although to this day, Night on Bald Mountain is still usually heard in Rimsky’s recomposition).

Modest Mussorgsky (1839-1881) also showed early talent, but nothing like the precocity of Enescu and Mendelssohn. And once he reached his maturity, he was burdened with a reputation as an artist who, despite his imagination, was deficient in terms of craft—a criticism never leveled at Enescu or Mendelssohn. Even Rimsky-Korsakov, one of his greatest advocates, referred to his “utter technical impotence.” Mussorgsky’s colleagues thus thought the best way to support his work was to refine it—and for years after his death, his music was heard primarily in editions that cleaned up his supposed faults. Only later did his nonconformity come to be appreciated (especially, at first, in France) as ingenuity rather than error. Nowadays, you’re far more likely to hear Mussorgsky’s own rough voice, rather than Rimsky-Korsakov’s splashier and more cultivated voice, when you listen to his opera Boris Godunov (although to this day, Night on Bald Mountain is still usually heard in Rimsky’s recomposition).

Pictures at an Exhibition, Mussorgsky’s most popular work, has the most complicated history of editorial interventions. Its inspiration came in 1874, when the critic Vladimir Stasov organized a retrospective of works by the short-lived Russian artist and architect Viktor Hartmann. Mussorgsky was a friend of both Stasov and the artist, and he commemorated the show with a piano cycle offering musical evocations of selected pictures, several of them separated by “promenades” representing the composer’s clumsy gait as he walks through the gallery. When the work first appeared in print, Stasov’s guide to the music was included; you can find it an appendix below.

Pictures wasn’t published until after the composer’s death—in an edition (no surprise) with “corrections” by Rimsky. But that was just the beginning: A decade later, Mihail Tushmalov made an abridged version for orchestra, and that opened the floodgates. By now there are hundreds of adaptations for different performing forces, from solo guitar to xylophone, from alto sax and harp to bassoon quintet, from rock ensemble (most famously, the version by Emerson, Lake, and Palmer) to full orchestra.

Yet for over a century, out of all those hundreds of variants, by far the most popular has been the orchestration, based on Rimsky’s edition, made in 1922 by Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). It’s not without detractors—some (including conductor Leopold Stokowski) have criticized it for being too polished. But those complaints have had little impact on the work’s popularity. Indeed, while the piano version remains central to the piano repertoire, the Ravel Pictures, for many people, has become the standard version—a work, says Larry, that “never falls out of favor.” And in part because Ravel’s recasting (like most other adaptations) sounds so clearly 20th-century, the work has been removed from its original context.

Yet for over a century, out of all those hundreds of variants, by far the most popular has been the orchestration, based on Rimsky’s edition, made in 1922 by Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). It’s not without detractors—some (including conductor Leopold Stokowski) have criticized it for being too polished. But those complaints have had little impact on the work’s popularity. Indeed, while the piano version remains central to the piano repertoire, the Ravel Pictures, for many people, has become the standard version—a work, says Larry, that “never falls out of favor.” And in part because Ravel’s recasting (like most other adaptations) sounds so clearly 20th-century, the work has been removed from its original context.

That historical dislocation might not be entirely a bad thing, for two reasons. First, while the music has remained vibrant for nearly a hundred and fifty years, Hartmann’s art has not. Many of the pictures Mussorgsky celebrated have been lost, and those that remain do not, for most viewers, stand up to the music they inspired. As a result, one can argue that the music works better if it’s severed from the artworks that inspired it, allowing listeners more freedom to exercise their imaginations.

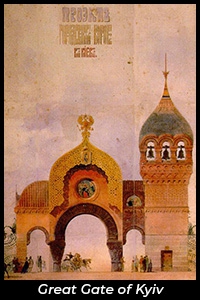

Second, Mussorgsky was a product of his times in ways that clash with contemporary values. Although it may have been be inspired by authentic Jewish melodies, “Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle” (probably based on two different Hartmann pictures) has elements of the anti-Semitism common in Russia at the time. As for “The Great Gate of Kyiv”: It’s a depiction of Hartmann’s sketches for an architectural idea never fulfilled, intended as a celebration of Tsar Alexander II. Although the titles of the individual movements of Pictures vary in language (including Italian, French, and Latin), Mussorgsky used the Russian, rather than the Ukrainian, spelling of Ukraine’s capital city (“Kiev” rather than “Kyiv”). And the music was clearly intended to exalt Russian imperialism at the expense of Ukrainian independence (although in the past few years, many people have repurposed it as a celebration of Ukraine—similar to the way Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture has been integrated into Fourth of July festivities).

Second, Mussorgsky was a product of his times in ways that clash with contemporary values. Although it may have been be inspired by authentic Jewish melodies, “Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle” (probably based on two different Hartmann pictures) has elements of the anti-Semitism common in Russia at the time. As for “The Great Gate of Kyiv”: It’s a depiction of Hartmann’s sketches for an architectural idea never fulfilled, intended as a celebration of Tsar Alexander II. Although the titles of the individual movements of Pictures vary in language (including Italian, French, and Latin), Mussorgsky used the Russian, rather than the Ukrainian, spelling of Ukraine’s capital city (“Kiev” rather than “Kyiv”). And the music was clearly intended to exalt Russian imperialism at the expense of Ukrainian independence (although in the past few years, many people have repurposed it as a celebration of Ukraine—similar to the way Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture has been integrated into Fourth of July festivities).

In any case, Ravel was the greatest orchestrator of his time; and Mussorgsky’s piano original is recast so imaginatively (for instance, the use of a saxophone to represent the troubadour in “The Old Castle” or the high tuba in the representation of an ox-cart in “Bydlo”) that few have been able to resist. It’s especially strong as a season opener, Larry notes, because it “shows off every corner of the orchestra and highlights musicians as soloists.” The closing, one of the grandest climaxes in the repertoire, is a rousing welcome to our eleventh season.

Peter J. Rabinowitz

Have any comments or questions? Please write to me at prabinowitz@ExperienceSymphoria.org

APPENDIX

When Pictures at an Exhibition was published in 1886, it included the following description by Vladimir Stasov. A few clarifying notes have been added in brackets.

The introduction is titled “Promenade.”

No. 1. “Gnomus”—a drawing, representing a small gnome, clumsily walking on small, crooked legs.

No. 2. “Il vecchio castello”—a castle of the Middle Ages before which a troubador sings his songs.

No. 3. “Tuileries: Argument among children after games”—An alley in the Tuileries garden, with a swirl of children and maids.

No. 4. “Bydlo”—a Polish cart on huge wheels, drawn by a yoke of oxen.

No. 5. “Ballet of the Chicks in their Shells”— a small painting by Hartmann for staging a picturesque scene from the ballet Trilbi.

No. 6. “Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle”—two Polish Jews, one rich and the other poor. [Note: “Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle” is the title in Mussorgsky’s manuscript, as well as in the first published edition and Ravel’s score. In Pavel Lamm’s edition of the score from 1930, the original title is eliminated—perhaps because it was thought to be offensive—and replaced in brackets by Stasov’s description.]

No. 7. “Limoges. The Market”—French women, arguing fiercely at the market.

No. 8. “Catacombae”—in Hartmann’s painting, he depicted himself gazing at the catacombs of Paris by the light of a lantern. In his original manuscript, Mussorgsky wrote above the Andante in B Minor, “The creative spirit of the dead Hartmann leads me toward the skulls he apostrophizes; the skulls light up gently from the inside.” [Note: The second half of this section, what Stasov called the Andante in B Minor, is subtitled “Con Mortuis In Lingua Mortua”—“With the Dead in a Dead Language.”]

No. 9. “The Hut on Chicken’s Legs”—Hartmann’s drawing represented a clock in the shape of the fantastic witch Baba Yaga’s small thatched cottage on chicken feet. Mussorgsky added the flight of Baba Yaga in a mortar.

No. 10. “The Great Gate of Kyiv”—Hartmann’s drawing represented his project for a door to the city of Kyiv in massive Russian-antique style, with a dome in the shape of a Slavonic helmet. [NOTE: The actual title of this movement in the score is “The Bogatyrs’ Gates (in the Capital in Kiev [sic]),” but it is most widely known these days as “The Great Gate of Kyiv.”)

[Note: Mussorgsky interleaved further Promenades after the first, second, fourth, and sixth pictures; Ravel eliminated the last of these. In addition, “Con Mortuis” and “The Great Gate” draw thematic material from the Promenade.]

FEATURED ARTISTS

Described as bringing an “artisan storyteller’s sensitivity… shaping passages with clarity and power via beautifully sculpted dynamics… revealing orchestral character not seen or heard before” (Arts Knoxville) Lawrence Loh enjoys a dynamic career as a conductor of orchestras all over the world.

After an extensive two ...

Described as bringing an “artisan storyteller’s sensitivity… shaping passages with clarity and power via beautifully sculpted dynamics… revealing orchestral character not seen or heard before” (Arts Knoxville) Lawrence Loh enjoys a dynamic career as a conductor of orchestras all over the world.

After an extensive two year search, Lawrence Loh was recently named Music Director of the Waco Symphony Orchestra beginning in the Spring of 2024. Since 2015, he has served as Music Director of The Syracuse Orchestra (formerly called Symphoria), the successor to the Syracuse Symphony Orchestra. “The connection between the organization and its audience is one of the qualities that’s come to define Syracuse’s symphony as it wraps up its 10th season, a milestone that might have seemed impossible at the beginning,” (Syracuse.com) The Syracuse Orchestra and Lawrence Loh show that it is possible to create a “new, more sustainable artistic institution from the ground up.”

Appointed Assistant Conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony in 2005, Mr Loh was quickly promoted to Associate and Resident Conductor within the first three years of working with the PSO. Always a favorite among Pittsburgh audiences, Loh returns frequently to his adopted city to conduct the PSO in a variety of concerts. Mr. Loh previously served as Music Director of the West Virginia Symphony Orchestra, Music Director of the Northeastern Pennsylvania Philharmonic, Artistic Director and Principal Conductor of the Syracuse Opera, Music Director of the Pittsburgh Youth Symphony Orchestra, Associate Conductor of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, Associate Conductor of the Colorado Symphony Orchestra and Music Director of the Denver Young Artists Orchestra.

Mr. Loh’s recent guest conducting engagements include the San Francisco Symphony, Dallas Symphony, North Carolina Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, Sarasota Orchestra, Florida Orchestra, Pensacola Symphony, Atlanta Symphony, National Symphony, Detroit Symphony, San Diego Symphony, Seattle Symphony, National Symphony (D.C.), Utah Symphony, Rochester Philharmonic, Indianapolis Symphony, Calgary Philharmonic, Buffalo Philharmonic, Albany Symphony and the Cathedral Choral Society at the Washington National Cathedral. His summer appearances include the festivals of Grant Park, Boston University Tanglewood Institute, Tanglewood with the Boston Pops, Chautauqua, Sun Valley, Shippensburg, Bravo Vail Valley, the Kinhaven Music School and the Performing Arts Institute (PA).

As a self-described “Star Wars geek” and film music enthusiast, Loh has conducted numerous sold-out John Williams and film music tribute concerts. Part of his appeal is his ability to serve as both host and conductor. “It is his enthusiasm for Williams’ music and the films for which it was written that is Loh’s great strength in this program. A fan’s enthusiasm drives his performances in broad strokes and details and fills his speaking to the audience with irresistible appeal. He used no cue cards. One felt he could speak at filibuster length on Williams’ music.” (Pittsburgh Tribune)

Mr Loh has assisted John Williams on multiple occasions and has worked with a wide range of pops artists from Chris Botti and Ann Hampton Callaway to Jason Alexander and Idina Menzel. As one of the most requested conductors for conducting Films in Concert, Loh has led Black Panther, Star Wars (Episodes 4-6), Jaws, Nightmare Before Christmas, Jurassic Park, Casablanca, The Wizard of Oz and Singin’ in the Rain, among other film productions.

Lawrence Loh received his Artist Diploma in Orchestral Conducting from Yale, his Masters in Choral Conducting from Indiana University and his Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Lawrence Loh was born in southern California of Korean parentage and raised in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He and his wife Jennifer have a son, Charlie, and a daughter, Hilary. Follow him on instagram @conductorlarryloh or Facebook at @lawrencelohconductor or visit his website, www.lawrenceloh.com

James Ehnes has established himself as one of the most sought-after musicians on the international stage. Gifted with a rare combination of stunning virtuosity, serene lyricism and an unfaltering musicality, Ehnes is a favourite guest at the world’s most celebrated concert halls.

Recent orchestral highlights include ...

James Ehnes has established himself as one of the most sought-after musicians on the international stage. Gifted with a rare combination of stunning virtuosity, serene lyricism and an unfaltering musicality, Ehnes is a favourite guest at the world’s most celebrated concert halls.

Recent orchestral highlights include the MET Orchestra at Carnegie Hall, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, San Francisco Symphony, London Symphony, NHK Symphony and Munich Philharmonic. Throughout the 23/24 season, Ehnes continues as Artist in Residence with the National Arts Centre of Canada and as Artistic Partner with Artis–Naples. During this season, he will make debuts with Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Tonhalle Zurich, and Israel Philharmonic Orchestra.

Alongside his concerto work, Ehnes maintains a busy recital schedule. He performs regularly at the Wigmore Hall (including the complete cycle of Beethoven Sonatas in 2019/20, and the complete violin/viola works of Brahms and Schumann in 2021/22), Carnegie Hall, Symphony Center Chicago, Amsterdam Concertgebouw, Ravinia, Montreux, Verbier Festival, Dresden Music Festival and Festival de Pâques in Aix. A devoted chamber musician, he is the leader of the Ehnes Quartet and the Artistic Director of the Seattle Chamber Music Society.

Ehnes has an extensive discography and has won many awards for his recordings, including two Grammy’s, three Gramophone Awards and eleven Juno Awards. In 2021, Ehnes was announced as the recipient of the coveted Artist of the Year title in the 2021 Gramophone Awards which celebrated his recent contributions to the recording industry, including the launch of a new online recital series entitled ‘Recitals from Home’ which was released in June 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent closure of concert halls. Ehnes recorded the six Bach Sonatas and Partitas and six Sonatas of Ysaÿe from his home with state-of-the-art recording equipment and released six episodes over the period of two months. These recordings have been met with great critical acclaim by audiences worldwide and Ehnes was described by Le Devoir as being “at the absolute forefront of the streaming evolution”.

Ehnes began violin studies at the age of five, became a protégé of the noted Canadian violinist Francis Chaplin aged nine, and made his orchestra debut with L’Orchestre symphonique de Montréal aged 13. He continued his studies with Sally Thomas at the Meadowmount School of Music and The Juilliard School, winning the Peter Mennin Prize for Outstanding Achievement and Leadership in Music upon his graduation in 1997. He is a Member of the Order of Canada and the Order of Manitoba, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, and an honorary fellow of the Royal Academy of Music, where he is a Visiting Professor.

Ehnes plays the “Marsick” Stradivarius of 1715.