We begin with Symphoria composed by our Principal Pops Conductor, Sean O’Loughlin. You’ll love Roberto Sierra’s colorful Fandangos and Duke Ellington’s Three Black Kings. Pianist Awadagin Pratt takes the stage to perform the New York premiere of Jessie Montgomery’s Rounds for Piano and String Orchestra. Kyle Bass joins Symphoria to speak the immortal words of Abraham Lincoln in Aaron Copland’s Lincoln Portrait.

PROGRAM

O’LOUGHLIN: Symphoria

SIERRA: Fandangos

MONTGOMERY: Rounds for Piano and String Orchestra

ELLINGTON: Three Black Kings

COPLAND: Lincoln Portrait ![]()

Thanks to our sponsors for this performance!

This project is made possible with funds from the City of Syracuse Arts & Culture Recovery Fund Program, a regrant program of the City of Syracuse and administered by CNY Arts.

Thank you to PEC Inc., our Masterworks Series Title Sponsor.

And to our Masterworks Series Media Sponsor, WRVO.

PROGRAM NOTES

Most of Symphoria’s classical repertoire consists of what’s called absolute music, music that exists without reference to anything outside it. But some of it (for instance, the Beethoven Sixth) is program music: instrumental music that tells a story or, in a less strict sense, that’s anchored in something non-musical. Tonight’s concert includes five examples of this looser type of program music, all by 20th-century composers from the United States. More specifically, all five celebrate people who have inspired their composers.

The most familiar is A Lincoln Portrait (1942) by Aaron Copland (1900–1990). It was an ...

Most of Symphoria’s classical repertoire consists of what’s called absolute music, music that exists without reference to anything outside it. But some of it (for instance, the Beethoven Sixth) is program music: instrumental music that tells a story or, in a less strict sense, that’s anchored in something non-musical. Tonight’s concert includes five examples of this looser type of program music, all by 20th-century composers from the United States. More specifically, all five celebrate people who have inspired their composers.

The most familiar is A Lincoln Portrait (1942) by Aaron Copland (1900–1990). It was an attempt to boost wartime spirits in difficult times; but unlike many occasional pieces, it has transcended the moment for which it was written. Stylistically, it has a lot in common with Copland’s Third Symphony, written a few years later, which closed our season last year. But in spirit, Lincoln Portrait is more defiant, less optimistically self-confident —and in its basic material, it makes more explicit use of traditional American tunes, which Copland avoided in the Symphony. He intended the opening to convey both “the mysterious sense of fatality that surrounds Lincoln’s personality” and “his gentleness and simplicity of spirit”; the middle section reflects “the background of the times he lived.” But the meat of the piece is the final part, given over to “the words of Lincoln himself,” with the music providing “a simple but impressive frame.”

Born a year before Copland, Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899–1974), too, stands as one of the greatest US composers of the 20th century. He’s commonly known, of course, as a jazz musician—but he disdained generic categories, and he wrote a great deal of symphonic music as well. His ballet Three Black Kings (1974) is his final work. In fact, he was still working on it in the hospital when he died (it was finished by his son Mercer). A eulogy for the Reverend Martin Luther King. Jr., the work begins with movements celebrating two earlier Black kings: Balthazar (one of the three Magi) and King Solomon. The first is dominated by driving rhythms; the second evokes the sensuality of the Song of Solomon in its outer sections, with a wilder dance between them. As for the finale: upbeat and gospel-infused, it infects us with the same kind of hope that Dr. King inspired.

The piece is crowned by sensational improvisations by the solo sax. Tonight’s soloist Charlie Young (who began as a classical sax player before expanding into jazz as well) points out that it’s “unfortunate that the art of improvisation, which was standard during Bach’s time and during the Classical period” has disappeared among classical players. As a result, many people misunderstand it, thinking that it’s just “making it up as we go along.” Rather, he starts from a “reservoir of learned things”—the musical equivalent of words—a reservoir shaped in part by his history and the spontaneity of the moment. Knowing where he is in a piece and where he wants to go allows those words to “rise to the surface and come from the instrument,” just as we find the words needed when speaking.

In Fandangos (2000), Roberto Sierra (b. 1953)—heralded by BBC Magazine as “the best Puerto Rican composer of all time”—takes his inspiration not from a spiritual or political leader, but from musical forbears. Specifically, he starts out from the famous Fandango for harpsichord by Spanish composer Antonio Soler, supplemented by the Fandango from the guitar quintet by Luigi Boccherini. Over the years, Symphoria has played many modern transcriptions and adaptations of earlier music: for instance, Stravinsky’s Pulcinella (based on music once attributed to Pergolesi) and the Bach “Suite” concocted by Mahler. Sierra does something different: Although Fandangos is rooted in orchestral color, it’s more than a dressing up of its sources. Rather, Soler and Boccherini—and the whole tradition of the fandango, one of the most familiar Spanish dances—serve as a springboard for an imaginative journey of Sierra’s own, one that, as the composer puts it, is “multidimensional”: “I bring [the fandango] to the present through some transformations of the musical fabric. When we are hearing something that may sound Baroque, a window into our time opens, and the piece is transformed.” Besides its brilliant veneer, its surprising shifts of perspective, and its virtuoso demands on the orchestra, it’s probably most notable for its hypnotic use of ostinatos (repeated musical patterns).

Ostinatos provide an aural link between Fandangos and our newest piece, Rounds for piano and strings. Composed by Symphoria regular Jessie Montgomery (b. 1981), it’s getting its New York premiere tonight. Like Fandangos, Rounds takes off from art of the past—in this case poetry. Specifically, Montgomery was inspired by a passage in T.S. Eliot’s “Burnt Norton” (from Four Quartets) that centers on the play of opposites and that, along with the work of biologist/philosopher Andreas Weber, helped her see the “interconnectedness of all things.” While working on the piece, Montgomery also became interested in, among other things, the patterns of bird flights, the infinite design of fractals, and the playing of pianist Awadagin Pratt, for whom the piece was written and who collaborated with her as she wrote it. All these influences found their way into the music.

Given Eliot’s reputation as a difficult poet, given the complexity of fractals and bird flights, you might expect something arcane—and there’s no doubt that Rounds is intricate. “Behind the scenes, a great deal of intellect went into its creation,” says Awadagin. “The craft of the piece is fantastic.” He’s been playing Rounds for a year; but, he says, “There are still things that I’m discovering, just in the internal mechanisms of the construction of the piece.” His phrase “behind the scenes,” though, is illuminating—because outwardly, “It’s not opaque. One can immediately embrace it. Even though there are a lot of things to listen for, things that a listener could focus on at a given moment, the overall thrust of where it’s going, what’s happening, is clear. The piece is not complicated to understand.” The overarching form is a rondo—a form in which a recurring section (called the “refrain”) is interrupted by contrasting music (“episodes”). And however Montgomery plays with that form, it’s easy to hear the oscillation between refrains and episodes. Then, too, the ostinatos—which drive the piece from the very beginning—give an immediate sense of purpose.

If Rounds is linked to Fandangos in its ostinatos, it’s linked to Three Black Kings in its turn to improvisation, since the cadenza—largely created by the soloist (Awadagin says that 99% of it is his)—is partially improvised. Since he started performing Rounds, “the cadenza certainly evolved. As I discover things internally, I showcase those things in the cadenza.” But changes are not limited to this long evolution—even “from a Friday to a Saturday to a Sunday, there’s going to be a 10-15% difference,” sometimes motivated by what else is on the program.

Audiences have been uniformly enthusiastic. Significantly, though, they’ve taken very different things from the music. “Some, responding to the propulsive energy of the piece, were buoyant,” says Awadagin. “Others said that it was the most beautiful thing they’d ever heard, that the music made them cry, that they went to unexpected places while listening to it.” A sign of just how rich Rounds is.

Our program opens with a tribute of yet another kind—a tribute to the people onstage. Pops Conductor Sean O’Loughlin (b. 1972) wrote his concert overture Symphoria back in December 2012 to launch the orchestra’s first official appearance under its current name. “The music,” says Sean, “shares the feeling of hope and joy of having orchestral music back in Central New York. The composition is an orchestral showpiece for the wonderful musicians of Symphoria and represents the spirit of ‘onward’ that has adorned the organization from the beginning.”

Peter J. Rabinowitz

Have any comments or questions? Please write to me at prabinowitz@ExperienceSymphoria.org

FEATURED ARTISTS

Among his generation of concert artists, pianist Awadagin Pratt is acclaimed for his musical insight and intensely involving performances in recital and with symphony orchestras.

Born in Pittsburgh, Awadagin Pratt began studying piano at the age of six. Three years later, having moved to Normal, Illinois with ...

Among his generation of concert artists, pianist Awadagin Pratt is acclaimed for his musical insight and intensely involving performances in recital and with symphony orchestras.

Born in Pittsburgh, Awadagin Pratt began studying piano at the age of six. Three years later, having moved to Normal, Illinois with his family, he also began studying violin. At the age of 16 he entered the University of Illinois where he studied piano, violin, and conducting. He subsequently enrolled at the Peabody Conservatory of Music where he became the first student in the school’s history to receive diplomas in three performance areas – piano, violin and conducting. In recognition of this achievement and for his work in the field of classical music, Mr. Pratt received the Distinguished Alumni Award from Johns Hopkins as well as an honorary doctorate from Illinois Wesleyan University after delivering the commencement address in 2012.

In 1992 Mr. Pratt won the Naumburg International Piano Competition and two years later was awarded an Avery Fisher Career Grant. Since then, he has played numerous recitals throughout the US including performances at Lincoln Center, the Kennedy Center, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles, Chicago’s Orchestra Hall and the NJ Performing Arts Center. His many orchestral performances include appearances with the New York Philharmonic, Minnesota Orchestra and the Pittsburgh, Atlanta, Baltimore, St. Louis, National, Detroit and New Jersey symphonies among many others. Summer festival engagements include appearances at Ravinia, Blossom, Wolftrap, Caramoor and Aspen and the Hollywood Bowl. Internationally, Mr. Pratt has toured Japan four times and performed in Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Poland, Israel, Columbia and South Africa.

Recent and upcoming appearances include recital engagements in Baltimore, La Jolla, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Ravinia, Lewes, Delaware, Duke University and at Carnegie Hall for the Naumburg Foundation; as well as appearances with the orchestras of Cincinnati, Indianapolis, North Carolina, Utah, Richmond, Grand Rapids, Memphis, Fresno, Winston-Salem, New Mexico, Rockford, IL and Springfield, OH. He also serves on the faculty of the Eastern Music Festival in Greensboro, North Carolina where he coaches chamber music, teaches individual pianists and performs chamber music and concertos with the festival orchestra.

Also an experienced conductor, Mr. Pratt has conducted programs with the Toledo, New Mexico, Vancouver WA, Winston-Salem, Santa Fe and Prince George County symphonies, the Northwest Sinfonietta, the Concertante di Chicago and several orchestras in Japan.

A great favorite on college and university performing arts series and a strong advocate of music education, Awadagin Pratt participates in numerous residency and outreach activities wherever he appears; these activities may include master classes, children’s recitals, play/talk demonstrations and question/answer sessions for students of all ages. He is also frequently invited to participate on international competition juries, such as the Rubinstein International Piano Master Competition in Israel, the Cleveland International Piano Competition, Minnesota e-Competition, the Unisa International Piano Competition in International Competition for Young Pianists in Memory of Vladimir Horowitz in the Ukraine.

In November 2009, Mr. Pratt was one of four artists selected to perform at a classical music event at the White House that included student workshops hosted by the First Lady, Michelle Obama, and performing in concert for guests including President Obama. He has performed two other times at the White House, both at the invitation of President and Mrs. Clinton.

Mr. Pratt’s recordings for Angel/EMI include A Long Way From Normal, an all Beethoven Sonata CD, Live From South Africa, Transformations and an all Bach disc with the St. Lawrence String Quartet. His most recent recordings are the Brahms Sonatas for Cello and Piano with Zuill Bailey for Telarc and a recording of the music of Judith Lang Zaimont with the Harlem Quartet for Navona Records.

Mr. Pratt is currently a Professor of Piano at the College-Conservatory of Music at the University of Cincinnati. He also served as the Artistic Director of the World Piano Competition in Cincinnati and is currently the Artistic Director of the Art of the Piano Festival at CCM.

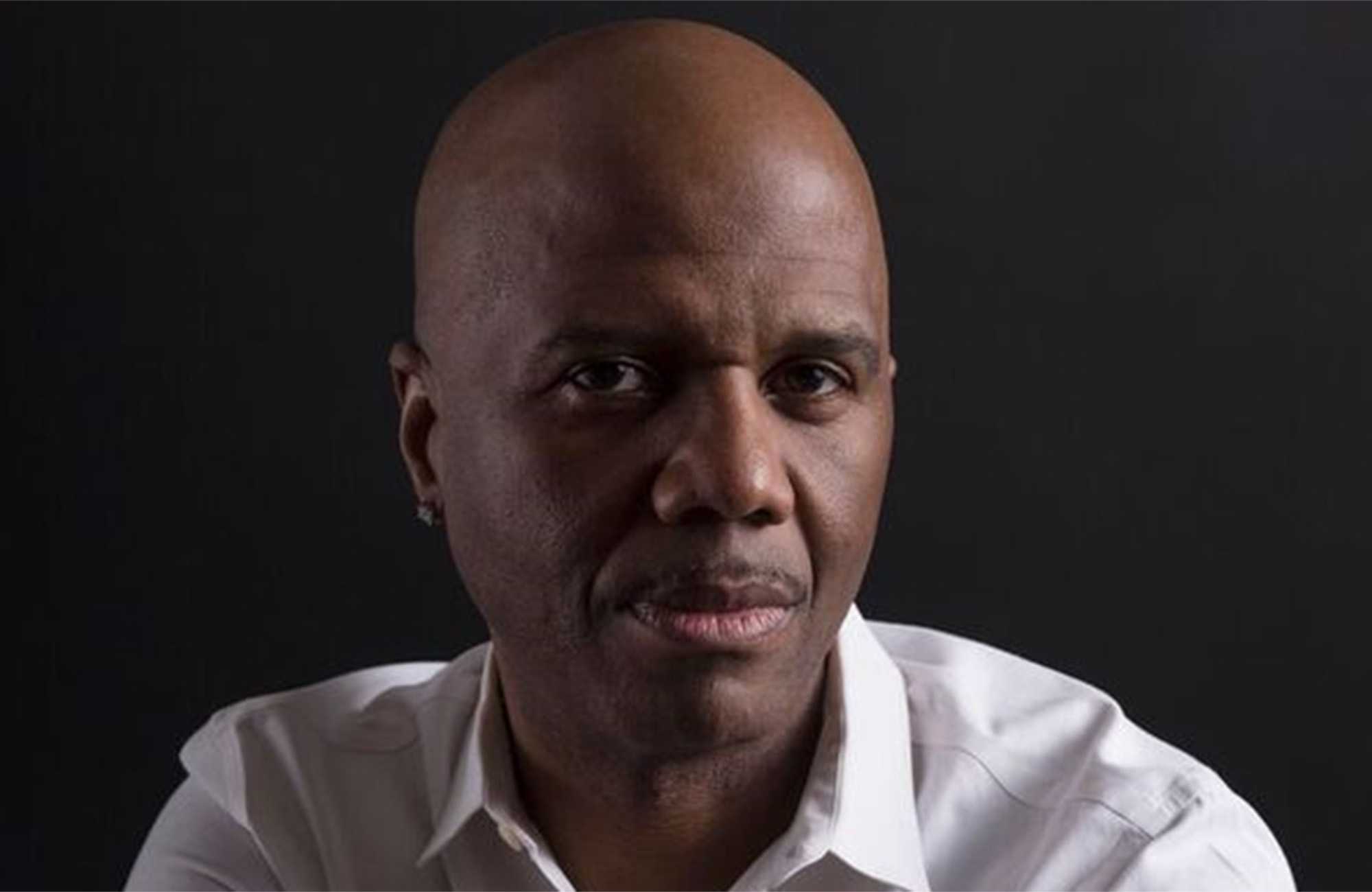

Charlie Young is a native of Norfolk, Virginia. Presently residing in the Washington, DC metropolitan region, he has served as Professor of Saxophone at Howard University for over 30 years, and is also Coordinator of Instrumental Jazz Studies.

Young has had a rich career performing and recording with ...

Charlie Young is a native of Norfolk, Virginia. Presently residing in the Washington, DC metropolitan region, he has served as Professor of Saxophone at Howard University for over 30 years, and is also Coordinator of Instrumental Jazz Studies.

Young has had a rich career performing and recording with various ensembles such as the National Symphony Orchestra, the US Navy Band, the Count Basie Orchestra and the Seattle Symphony Orchestra. Mr. Young has shared the concert stage with many of the music industry’s leading icons ranging from Clark Terry and Ella Fitzgerald to Stevie Wonder and Quincy Jones. Performance venues have ranged from London’s Royal Albert Hall to New York’s Carnegie Hall.

In 1988, Charlie Young was recruited as a member of the Duke Ellington Orchestra where he presently serves as Artistic Director/ Conductor, and lead saxophonist. Young joined the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra in 1995 serving as the ensemble’s principal woodwind specialist for over 15 years. In 2013, he was appointed Artistic Director and Conductor.

In addition to working with legendary ensembles, Young and his jazz quintet performed at the 1988 San Remo Jazz and Blues Festival as musical ambassador for Washington DC. In 2008, he was invited to present an inaugural concert and lecture at the opening of the New American University in Cairo, Egypt. Mr. Young is published on over 30 CD recordings, including his solo release “So Long Ago.”

Young is a recognized clinician in the field of jazz education as well as in classical and jazz saxophone performance. Clinic presentations in Brazil, Venezuela, Chile, Egypt, Kenya, South Africa, Singapore, and throughout the United States, Europe and Japan has earned Charlie Young a stellar reputation among the most respected in saxophone performance and education.

Kyle Bass is the author of the play “Salt City Blues” which was produced at Syracuse Stage in the 21/22 season, “Citizen James, or The Young Man Without a Country”, about a young James Baldwin, which was commissioned by Syracuse Stage, has streamed nationally since 2021 and has been optioned for ...

Kyle Bass is the author of the play “Salt City Blues” which was produced at Syracuse Stage in the 21/22 season, “Citizen James, or The Young Man Without a Country”, about a young James Baldwin, which was commissioned by Syracuse Stage, has streamed nationally since 2021 and has been optioned for a feature-length film, and “Possessing Harriet”, which premiered at Syracuse Stage, was subsequently produced at Franklin Stage Company and at the East Lynn Theater Company, and was published by Standing Stone Books in 2022. His play “Tender Rain” will premiere at Syracuse Stage in May. His newest play “Toliver & Wakeman”, commissioned by Franklin Stage Company through a Support for Artist Grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, will premiere at Franklin Stage Company in August. Kyle also wrote the libretto for “Libba Cotten: Here This Day”, an opera based on the life of American folk music legend Libba Cotten, commissioned by The Society for New Music. With Ping Chong, Kyle is the co-author of “Cry for Peace: Voices from the Congo”, which premiered at Syracuse Stage and was subsequently produced at La MaMa Experimental Theatre in New York. Kyle also worked with Ping Chong and Sara Zatz on “Tales from The Salt City”, which premiered at Syracuse Stage. Kyle’s other full-length plays include “Leeboe and Sons”, “Baldwin vs. Buckley: The Faith of Our Fathers”, which has been presented at Cornell University, Colgate University, the University of Delaware, and Syracuse University, and “Separated”, a documentary theatre piece about the student military veterans at Syracuse University, which was presented at Syracuse Stage and the Paley Center in New York. He has also written for Noh theatre under commission by Theatre Nohgaku.

Kyle is the co-author of the original screenplay for the film “Day of Days” (Broad Green Pictures, 2017) and is a three-time recipient of the New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship (for fiction in 1998, for playwriting in 2010, and for screenwriting in 2022), a finalist for the Princess Grace Playwriting Award, and a Pushcart Prize nominee. As dramaturg, Kyle worked with acclaimed visual artist and MacArthur “Genius” Fellow Carrie Mae Weems on her theatre piece “Grace Notes: Reflections for Now”, which premiered at the 2016 Spoleto Festival USA, and he was the script consultant on “Thoughts of a Colored Man”, which premiered at Syracuse Stage in 2019 and opened on Broadway in 2021. His plays and other writings have appeared in the journals Callaloo and Stone Canoe, among others, and in the anthology “Alchemy of the Word: Writers Talk about Writing”. Kyle is an assistant professor in the Department of Theater at Colgate University, where he was the 2019 Burke Endowed Chair for Regional Studies. Previously, he was faculty in the MFA Creative Writing program at Goddard College, taught playwriting in the Department of Drama and theater and dramatic literature courses in the Department of African American Studies at Syracuse University, and playwriting at Hobart & William Smith Colleges. The 2019/20 Susan P. Stroman Visiting Playwright at the University of Delaware and the 2023 Flournoy Visiting Playwright at Washington & Lee University, Kyle holds an MFA in playwriting from Goddard College, is a proud member of the Dramatists Guild of America and is represented by the Barbara Hogenson Agency. A descendant of African people enslaved in New England and the American South, Kyle lives and writes in upstate New York where his family had lived free and owned land for nearly 225 years.

Described as bringing an “artisan storyteller’s sensitivity… shaping passages with clarity and power via beautifully sculpted dynamics… revealing orchestral character not seen or heard before” (Arts Knoxville) Lawrence Loh enjoys a dynamic career as a conductor of orchestras all over the world.

After an extensive two ...

Described as bringing an “artisan storyteller’s sensitivity… shaping passages with clarity and power via beautifully sculpted dynamics… revealing orchestral character not seen or heard before” (Arts Knoxville) Lawrence Loh enjoys a dynamic career as a conductor of orchestras all over the world.

After an extensive two year search, Lawrence Loh was recently named Music Director of the Waco Symphony Orchestra beginning in the Spring of 2024. Since 2015, he has served as Music Director of The Syracuse Orchestra (formerly called Symphoria), the successor to the Syracuse Symphony Orchestra. “The connection between the organization and its audience is one of the qualities that’s come to define Syracuse’s symphony as it wraps up its 10th season, a milestone that might have seemed impossible at the beginning,” (Syracuse.com) The Syracuse Orchestra and Lawrence Loh show that it is possible to create a “new, more sustainable artistic institution from the ground up.”

Appointed Assistant Conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony in 2005, Mr Loh was quickly promoted to Associate and Resident Conductor within the first three years of working with the PSO. Always a favorite among Pittsburgh audiences, Loh returns frequently to his adopted city to conduct the PSO in a variety of concerts. Mr. Loh previously served as Music Director of the West Virginia Symphony Orchestra, Music Director of the Northeastern Pennsylvania Philharmonic, Artistic Director and Principal Conductor of the Syracuse Opera, Music Director of the Pittsburgh Youth Symphony Orchestra, Associate Conductor of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, Associate Conductor of the Colorado Symphony Orchestra and Music Director of the Denver Young Artists Orchestra.

Mr. Loh’s recent guest conducting engagements include the San Francisco Symphony, Dallas Symphony, North Carolina Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, Sarasota Orchestra, Florida Orchestra, Pensacola Symphony, Atlanta Symphony, National Symphony, Detroit Symphony, San Diego Symphony, Seattle Symphony, National Symphony (D.C.), Utah Symphony, Rochester Philharmonic, Indianapolis Symphony, Calgary Philharmonic, Buffalo Philharmonic, Albany Symphony and the Cathedral Choral Society at the Washington National Cathedral. His summer appearances include the festivals of Grant Park, Boston University Tanglewood Institute, Tanglewood with the Boston Pops, Chautauqua, Sun Valley, Shippensburg, Bravo Vail Valley, the Kinhaven Music School and the Performing Arts Institute (PA).

As a self-described “Star Wars geek” and film music enthusiast, Loh has conducted numerous sold-out John Williams and film music tribute concerts. Part of his appeal is his ability to serve as both host and conductor. “It is his enthusiasm for Williams’ music and the films for which it was written that is Loh’s great strength in this program. A fan’s enthusiasm drives his performances in broad strokes and details and fills his speaking to the audience with irresistible appeal. He used no cue cards. One felt he could speak at filibuster length on Williams’ music.” (Pittsburgh Tribune)

Mr Loh has assisted John Williams on multiple occasions and has worked with a wide range of pops artists from Chris Botti and Ann Hampton Callaway to Jason Alexander and Idina Menzel. As one of the most requested conductors for conducting Films in Concert, Loh has led Black Panther, Star Wars (Episodes 4-6), Jaws, Nightmare Before Christmas, Jurassic Park, Casablanca, The Wizard of Oz and Singin’ in the Rain, among other film productions.

Lawrence Loh received his Artist Diploma in Orchestral Conducting from Yale, his Masters in Choral Conducting from Indiana University and his Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Lawrence Loh was born in southern California of Korean parentage and raised in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He and his wife Jennifer have a son, Charlie, and a daughter, Hilary. Follow him on instagram @conductorlarryloh or Facebook at @lawrencelohconductor or visit his website, www.lawrenceloh.com